Exploring the World Through Music

Why does music sound different in different parts of the world?

Music is an essential part of the human experience. Our brains are hardwired for it and every civilization on Earth has created their own unique music culture. Much like language, people in different parts of the world have found an almost endless diversity of ways to organize noise across time - i.e.: make music. How we organize that noise - and what noise we choose to organize - is what gives our different musical traditions their unique sound. One of the most noticeable differences between music traditions is different patterns of notes, or scales, they use.

What is a scale?

A scale is more than just an exercise you sing or play. Scales are the building blocks of music. They are the answer to the question that every music culture on earth has asked itself, “How do we subdivide the octave?” In European art music, the answer to that question was to divide the octave into twelve semitones or half steps, arranged into 8 note patterns that form the major and minor scales you’re most likely familiar with. A less technical way to understand scales is to think of the notes in a scale as the palette of colors we use to paint a song; we might play two notes at once and mix colors to create a new shade or play two contrasting notes one after the other so that their colors can compliment each other, but we’re limited to the colors in our palette.

If you’ve taken music lessons in the United States or another English speaking country, there’s a good chance that the only palette of colors you’ve ever gotten to paint with are the major and minor scales of European art music. Don’t get us wrong, you can make incredible music with those scales, but it can also feel like only ever eating vanilla ice cream or only ever having the basic box of 8 crayons. Luckily, the major and minor scales we’re most familiar with are just one of many answers to the problem of dividing up the octave. Cultures around the world have come up with different solutions to the octave problem ranging from five-note pentatonic scales that have been found from Asia to the Americas for the past 50,000 years to twenty-two-note microtonal scales in Indian classical music. There are thousands of musical color palettes to draw from; no need to limit yourself to the basic crayon box.

Below we’ll share some scales you can start exploring that use the same half step intervals found in European art music as well as briefly discuss some microtonal scales if you want to dive in deeper.

Pentatonic scales

Pentatonic or five-note scales are some of the oldest ways to divide up the octave found in musical traditions of Europe, East and South East Asia, Africa, and the indigenous peoples of both North and South America. The two you’re mostly likely to hear in American roots music are the major and minor pentatonic scales. These scales are most closely related to the major and minor scales you’ve most likely learned about in your school music class. Here’s what the scales look like in music notation.

You’ve almost definitely heard songs that use the major pentatonic scale before. “Amazing Grace,” “My Girl” by The Temptations, and “Cotton Eye Joe” by Rednex are all written in major pentatonic while Ed Sheeran’s “Shape of You” is in minor pentatonic.

Of course, major and minor aren’t the only variations of the pentatonic scale; this is arguably the oldest and most widely used way to divide up the octave after all. Two versions of the pentatonic scale are used in Japanese music, the min’yō scale and the hon-kumoi-joshi. You can see them represented in western music notation below.

It’s important to note that all of these pentatonic scales have different names in different cultures. For example, the min’yō scale is often called the blues major scale in the United States, ambassel in Ethiopian musical traditions, and corresponds to the South Indian raga Shuddha Saveri.

Modes

There are seven diatonic modes in western music which include the major and minor scales you’re familiar with. A mode uses the same notes as a major scale but starts from a different note in the scale. For example, D dorian is a C major scale but played starting and ending on the second scale degree, D. Below are examples of all seven modes. Note that Ionian mode is the same as the major scale and Aeolian is another name for the minor scale.

Modes show up all over contemporary American music and correlate to scales found in folk music traditions in Europe and other parts of the world. For example, Irish music frequently uses Dorian and Mixolydian modes. Nelly’s “Hot in Herre” borrows from both Phrygian and Dorian mode, Lorde’s “Royals” is in Mixolydian, and “Baby Got Back” by Sir Mix-A-Lot is in Phrygian.

Harmonic Minor and Major

Both harmonic minor and major can be described as altered versions of the standard minor and major scales. To our ears in Western Europe and the United States, they can sound Arabic, but these scales don’t originate in those parts of the world; rather, they approximate some of the colors found in the microtonal scales of Arabic and Persian music. Here are examples of these scales in music notation:

Harmonic minor is more commonly used in modern music, appearing in Jazmine Sullivan’s “Bust Your Windows” and is blended with natural minor in “Santeria” by Sublime. Harmonic major often turns up in guitar riffs and is borrowed from and blended with natural major scales in several Beatles tunes including “I Saw Her Standing There” and the dreamy verses of “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.”

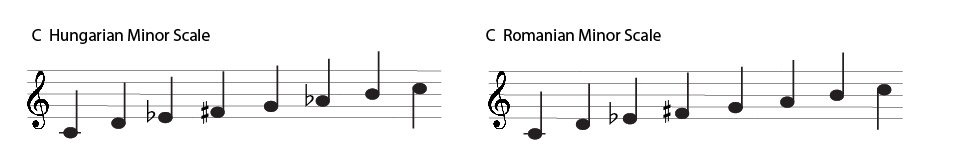

Hungarian Minor and Romanian Minor

Hungarian minor and Romanian minor have several names and, while you might not be familiar with any of their aliases, you’ve probably heard the scales before before. Both might bring to mind Eastern European or klezmer music. Here are both scales written out in music notation:

Romanian minor is frequently used in klezmer music and is called Mi sheberach when used in Jewish liturgical music. Hungarian minor can be heard in the saxophone riff on “Worth It” by Fifth Harmony as well as numerous rock, jazz, and classical pieces including “Musterion” by Joe Satriani and Tchaikovsky’s “Marche slave.”

Microtonal Scales

Microtonal scales use intervals smaller than the semitones you may be accustomed to hearing in European and American music. The classical musics of India, Japan, Indonesia, and Turkey notably use microtonal scales, with the classical Turkish makam system recognizing 53 intervals in an octave. Some experimental jazz, rock, and electronic musicians also use microtones; for example, Radiohead’s “How To Disappear Completely” uses microtonal string arrangements. Microtonal music has its own unique approach to harmony and notation, and can feel a little bit like seeing a new color if you grew up in a music culture that only uses semitones. While we won’t go into great detail here, we highly recommend going down the microtonal rabbit hole if the idea intrigues you.

What do I do with these scales?

Scales are kind of an abstract concept; most real music doesn’t consist of just running up and down a scale nor do composers always limit themselves to just one scale when writing a song. There are “rules” to music, but there aren’t harmony police who make sure you follow them. At the end of the day, music is an art form and the important thing is how it makes you feel, not how perfectly it follows a formula. People didn’t invent scales and then write music based off them, they wrote music that made them feel something and then figured out what notes they had used and made a scale out of them.

Despite that, exploring different scales can open your ears and mind to new sounds. If you’re a songwriter - or if you’ve always wanted to try songwriting and don’t know where to start - making a melody out of an unfamiliar scale can get creative juices flowing or spark unexpected inspiration.

Different scales can also add interest to stale vocal exercises. For example, instead of singing your exercises on a major scale (as the vast majority of vocal exercises are written), substitute a mode or altered scale. Singing your warmups using an Hungarian minor scale, for example, adds a challenging element of ear training to your vocal practice. That ear training can ultimately help you improve your pitch accuracy and make it easier to learn new songs by ear.

Start Your Musical Journey by Booking a Lesson Today

Understanding different scales can change how we appreciate music - and other music cultures. Music and food are two of the most accessible ways to start learning about another culture. Diving deeper into microtonal scales might lead to learning more about the cultures they originate in; we had a hard time not diving deeper into the classical Turkish harmony system while researching this article. We hope that exploring the sounds of distant places both transports and inspires you the way it has us.

If you want a guide on your musical journey, reach out and schedule a lesson with Zelda. Explore all you can and love your voice!

If you want a tour guide on your musical journey around the world, book a lesson with Zelda today!

Mention this article for a 20% discount on your first lesson.

If you’d like to improve your voice using scales and exercises, check out our Vocal Workout program here.